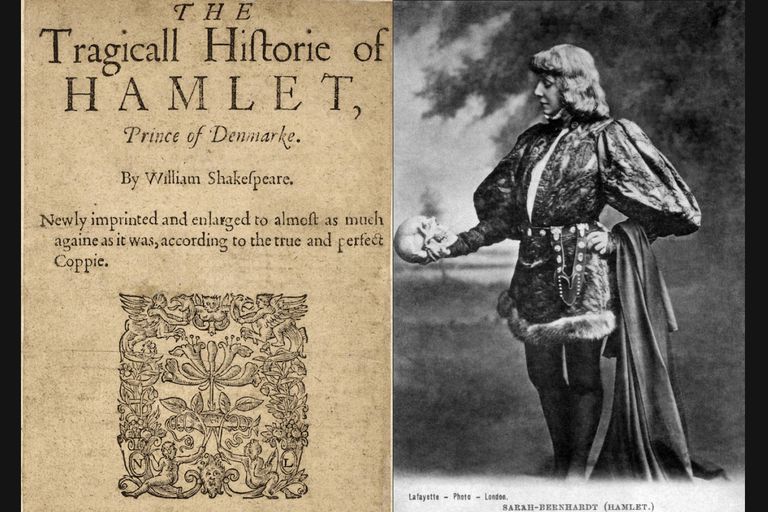

Shakespeare’s plays have been analyzed for many years, and the similarity of almost all analysis is that Shakespeare constructed his plays as a play-within-a-play. Among the many reasons that we can state for such a structuring, one of it is to point to the function of performance, which was to emphasize truth and bring out reality. Whether it was through the duality of characters, conflict of interest, misconception, and understanding, it seems that Shakespeare’s plays each point to a specific direction: the art of theater and its impact on both the audience and the actors themselves. Being so, Hamlet is one of Shakespeare’s masterpiece that embodies the duality and conflict of a character, who construct a play within his performance, much like Shakespeare, to bring out the truth. The pretense of madness and the performance of this madness in Shakespeare’s Hamlet creates a difference between reality and imagination, truth, and performance and thereby unveils the tools of theatre.

Hamlet is constructed as a play within a play, a performance for the sake of another performance. In the introduction of the character Hamlet, we see a character which moves the boundaries of performance and reality. His mother, Queen Gertrude asks her son why he is so grieved that he “seems… so particular” (Shakespeare 25), however, he ignores her point, because he is deeply concerned with his performance, and responds to her word ‘seeming’ by saying,

Seems, madam? nay, it is, I know not ‘seems.’

’Tis not alone my inky cloak, [good] mother,

Nor customary suits of solemn black,

Nor windy suspiration of forc’d breath,

No, nor the fruitful river in the eye,

Nor the dejected havior of the visage,

Together with all forms, moods, [shapes] of grief,

That can [denote] me truly.

These indeed seem,

For they are actions that a man might play,

But I have that within which passes show,

These but the trappings and the suits of woe.’ (Shakespeare 25-26)

Hamlet argues that showing the emotions openly for everyone to see makes the person untrustworthy, because the same person, who reveal the emotions, could also be performing or mimicking the genuine feelings. Hamlet’s true feeling and thought about his father’s death and Claudius and the Queen are all demonstrations of being upset since Hamlet believes that performance of emotions is the only way he could get the murderers to confess. Therefore, Hamlet insists that what he wears, his mimics and his tears do not mean anything, these details seem to reflect his grief, because his real meaning lies in his internal self and inner feelings. Hamlet is obsessed with ‘show’ and ‘originality, ‘real’ and ‘performance’ throughout the play. When he finds out the truth about the murder of his father by his uncle, Hamlet sees it as a lesson on appearances that are artificial, mainly his uncle: ‘meet it is I set it down / That one may smile, and smile, and be a villain!’ (Shakespeare 63) The simple differences between performance and originality, shoe and authenticity are covered with the tragedy. Hamlet cannot let go of his desire to perform, even though previously he had reacted to being ‘seeming’ in a snappish and bad-tempered outburst. He manages to attain an ‘antic disposition’ (Shakespeare 67) to distract his audience from his revenge idea, at the same time, his unlimited grieving and complaining make he appear as though he is over-acting his own plotted performance. At the moment where Hamlet is meditating on ‘that within which passes show,’ Hamlet argues firmly that he is mourning for his father and that his internal grief is for real, although he seems to be deliberately showing his mourning for the authentic audience and also the intended audience- Claudius. With his performance in performance and the structure of a play in a play, Shakespeare, through Hamlet, manages to discover how performance emphasizes reality and alters it in a way that brings out the truth.

Even though Hamlet dislikes the art of performance and the act of ‘seeming,’ his enthusiastic reaction to the players when they come to performs shows his passion for performance and theatre. He is left in shock when the actors give a speech about Troy, and it’s destruction, upon Hamlet’s urge:

Is it not monstrous that this player here,

But in a fiction, in a dream of passion,

Could force his soul so to his conceit

That from her working all his visage wann’d …

What’s Hecuba to him, or he to [Hecuba],

That he should weep for her?

What would he do

Had he the motive and [the cue] for passion

That I have?

He would drown the stage with tears,

And cleave the general ear with horrid speech,

Make mad the guilty, and appall the free. (Shakespeare 117)

In these lines, we see Hamlet is left in a conflict between performance and authenticity, a relationship he sees as ‘monstrous.’ Hamlet is amazed by the actor’s performance that manages to force real tears coming from his very soul into a role that is fictional and unauthentic. In this sense, the actor’s performance involves the hint of reality in it, while at the same time doing a good job in performing to grieve. The performance of the players is more convincing that Hamlet’s reaction when he learns that Claudius was the murderer of his father. Hamlet starts to question the truth that would come out of the art of performance: If the player had Hamlet’s experience, cause, reason, how would his talents reveal the courtly corruption. In this sense, Hamlet’s plan to “catch the conscience of the King” (Shakespeare 119) is explained. Targoff says in his article, “… the external performative behavior might serve as both a criterion of outward judgment and a vehicle of inward change.” (Targoff 64) After the moment where Hamlet learns of his uncle’s murder of his father, his outward actions start to shape his inner thoughts and feelings. For one thing, he plots revenge, through performance. This shows that he will be portraying an attitude that is not real, but can be a criterion for his, yet what he fails to realize that this behavior that is shaped by his subjective judgment will be a tool that will also change his inner emotions, and moreover, his inner self.

Even though he is not sure if the Ghost’s story about his father is true, Hamlet starts to rely on performance and theatre and its skill in bringing out reality through performance to get his revenge:

I have heard

That guilty creatures sitting at a play

Have by the very cunning of the scene

Been strook so to the soul, that presently

They have proclaim’d their malefactions. (Shakespeare 119)

Although the theatre is merely a performance of feelings and thought, it still creates an impact that is inevitable and very real in its audience. Hamlet, an actor in a play, was very well aware of this effect of theatre, which is why he chose performance and theatre as a way to bring out the truth about his father’s death. Shakespeare does an excellent job in writing, and the actors are successful in performing the plot of the play, but a deception is also a useful tool that helps both the actors and the writer to mirror the murder and the confession. Targoff seems to refer to the use of the deception tool in his article when he talks about Claudius’s prayer and confession, “And yet, while the theater succeeds in provoking an unprecedented attempt at pious behavior, the devotional performance that ensues falls short of the mark: Claudius’s prayer turns out to be only a performance…” (Targoff 62) In this sense, the border between performance and reality is a thin line, which is probably why performance is an excellent way to bring out the truth. Hamlet uses the play The Murder of Gonzago very cleverly so that he could observe Claudius as the crime in the play is performed, his feelings and thoughts revealed through his mimics and actions. Thus, we see Hamlet believing in the impact of theatre as having real and truthful effects on its audience.

The flip side at this point is what Targoff claims in his article, “that what began as a purely hypocritical performance would become a transformative experience.” (Targoff 52) Eventually, Hamlet will be transformed into the character that he has sought revenge- a murderer. In this sense, the performance that he planned and also found untrustworthy turns on him, transforming him from a mourning innocent son to a revengeful murderer. The audience is not shown the actual act of murder happening on stage- we do not see Hamlet being murdered, nor do we see Claudius kill Hamlet’s father. The structure that Shakespeare has built on, the play-within-a-play, keeps the audience away from the truth about the king, which makes the performance even more convincing and also frustrating.

Moreover, the character of the poisoner in the play, The Murder of Gonzago, is a mixture of Claudius and Hamlet. Hamlet defines this character as a ‘nephew’ and not a brother of the king, who is to be murdered by his nephew. At this point, we see the ethical problem of revenge that lies within the play: the revenger becomes a criminal himself, just like the murderer. Hamlet strategy of performance-within-a-performance allows him to judge Claudius but also becomes a starting point for the one who will revenge Hamlet’s death. He starts to see his father’s murder and also the future-death of his uncle, for the sake of his revenge. At this point, theatre is both attacked and defended by Shakespeare, because it plays on the morality of Claudius’s consciousness and at the same time tries to convince Hamlet to commit an immoral sin. In the beginning, Hamlet had found the act of ‘seeming’ to be deceptive and immoral, but the way he deals with the situation is merely performative.

In its entirety, the construction of the play is what makes the play convincing but also a tragedy. If it had not been for Hamlet’s performance to seek revenge, if it had not been Claudius’s performance of acting innocent, and if it had not been Gertrude’s performance of a loving wife and mother; the play would not be a tragedy, but a mere story of a father murdered and a son avenging the death of his father. It is the movement of the back and forth between performance and reality that places the play on the verge of being a moral lesson, but also the entertainment of performance. As Hamlet goes back and forth between his real self and the avenging Hamlet, the audience is confused but also amused to see that an actor can construct a play within a play. Shakespeare manages to adapt the relationship between authenticity and show through Hamlet, who adapts the relationship between reality and theatre as a symbol of the former. In this sense, Hamlet’s performance becomes a part of the reality that he and also Shakespeare seeks to find.

Works Cited

Shakespeare, William. Hamlet. Ed. Barbara A. Mowat and Paul Werstine. Folger Shakespeare Library, 2012.

Targoff, Ramie. “The Performance of Prayer: Sincerity and Theatricality in Early Modern England.” Representations 60 (1997): 49-69.